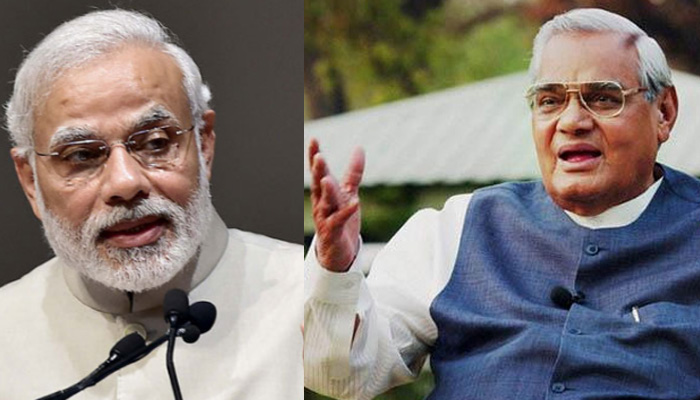

Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi are great leaders of the same party, but differ drastically in style of functioning. Who is greater?

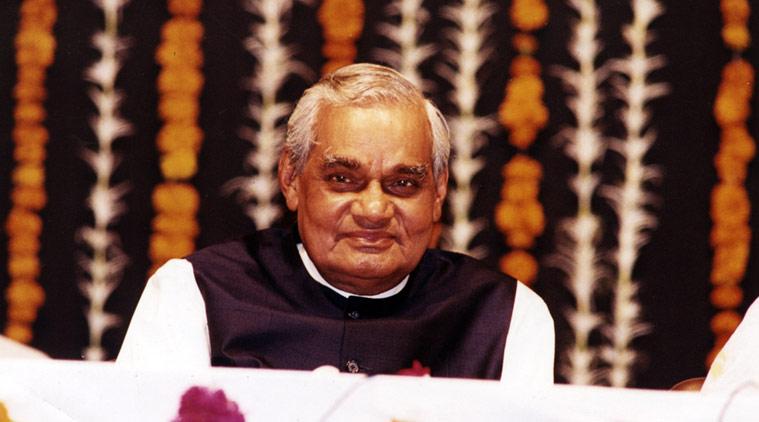

As former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee turned 93 on Christmas day, there were no celebrations to tom-tom about. Like PV Narasimha Rao of the Congress, Vajpayee is being deliberately pushed into the pages of history; so it seems.

As former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee turned 93 on Christmas day, there were no celebrations to tom-tom about. Like PV Narasimha Rao of the Congress, Vajpayee is being deliberately pushed into the pages of history; so it seems.

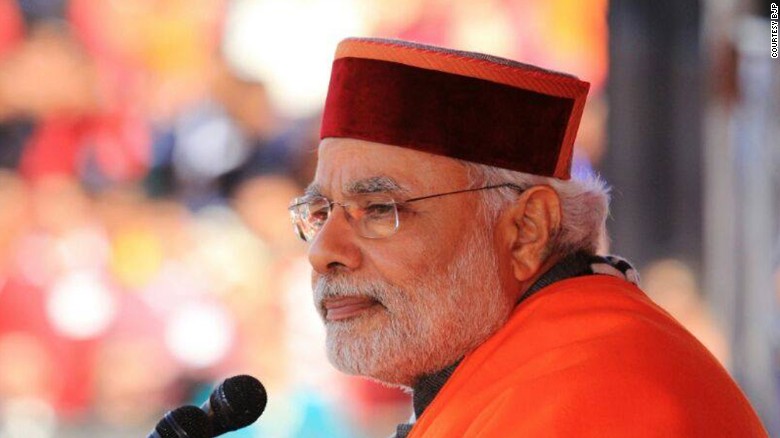

But it would be pertinent to compare him with the present prime minister Narendra Modi to bring out his qualities. Both grew up under the RSS and were nurtured by the BJP. Both were good orators and grew up the hard way to the top. Their powerful oratory had and has the capacity to bind the audience. The difference: Vajpayee spoke to your heart whereas Modi speaks to your brain. Vajpayee could occasionally even make you weep with his speeches, Modi can never; Modi would make you think. Vajpayee was a poet, he could say a lot with so few words. Modi has to use many words to convey a point.

Both the leaders never depended on a written text to speak from the ramparts of the Red Fort or elsewhere. They were born orators.

The RSS background, BJP grooming and oratory may be a common, but the comparison ends there.

Many in young India may not have had the privilege to listen to Vajpayee or know about the way he functioned. It may also sound strange that while Modi recalled the contributions made by Congress stalwart Sardar Vallabhai Patel during the recent Gujarat elections, he did not say a single word about Vajpayee.

Many in young India may not have had the privilege to listen to Vajpayee or know about the way he functioned. It may also sound strange that while Modi recalled the contributions made by Congress stalwart Sardar Vallabhai Patel during the recent Gujarat elections, he did not say a single word about Vajpayee.

Vajpayee had a great respect for institutions, especially the Parliament. He never ran away. He would debate and lose, but never give up. Modi, on the other hand, kept away from Rajya Sabha on many occasions as the BJP was in a minority and he was not comfortable facing the carping criticism from people like Sitaram Yechury, Sharad Yadav and Mayawati.

Vajpayee belongs to the older generation of leaders like L K Advani and Murali Manohar Joshi. The three did not have great opinion about Modi. It would not be out of place that Modi still nurtures a hidden hatred for Vajpayee who had asked him to resign following the Gujarat riots.

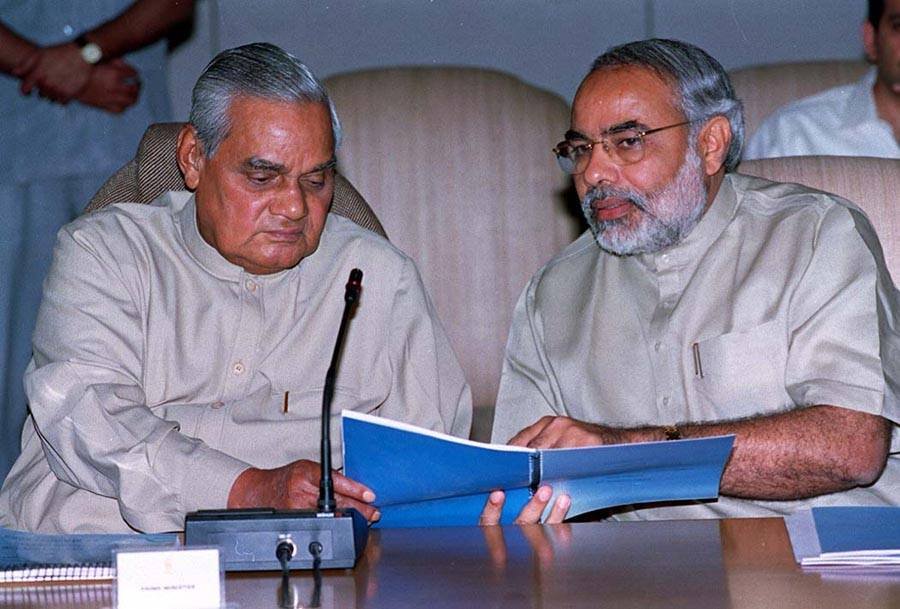

Post Gujarat riots, Modi became more aggressive and disagreed with Vajpayee’s brand of accommodative politics. While Vajpayee appealed to a wider political spectrum, Modi’s spectrum was much narrower and focused on the Hindutva agenda. Modi was so brash that after the Gujarat riots he dared to publicly snub Vajpayee at a press conference where he was seated alongside the prime minister.

Post Gujarat riots, Modi became more aggressive and disagreed with Vajpayee’s brand of accommodative politics. While Vajpayee appealed to a wider political spectrum, Modi’s spectrum was much narrower and focused on the Hindutva agenda. Modi was so brash that after the Gujarat riots he dared to publicly snub Vajpayee at a press conference where he was seated alongside the prime minister.

At the press conference, a reporter wanted to know Vajpayee’s message for the chief minister in the wake of the riots. Vajpayee took a long time to answer keeping everyone guessing. Then in a display of controlled displeasure, he said Modi should ‘follow his Rajdharma’. With eyes closed and in a pensive mood, he went on to explain that Rajdharma was a meaningful term, and for somebody in a position of power, it meant not discriminating among the higher and lower classes of society or people of any religion.

Before Vajpayee could go further, Modi turned towards Vajpayee and in a strong note of threatening defiance said, ‘Hum bhi wahi kar rahe hain, sahib (That is what we are also doing, sir).’ Vajpayee was shocked at the defiance, but overcame it by saying ‘I am sure Narendrabhai is also doing the same.’

The second snub and defiance came during BJP’s national executive committee meeting in Goa in April 2002.

Modi probably got a clue that the political winds may go against his favour as Vajpayee, during a trip to Singapore before the Goa meeting, had told a press conference ‘Whatever happened in India was very unfortunate. The riots have been brought under control. If at the Godhra station, the passengers of the Sabarmati Express had not been burnt alive, then perhaps the Gujarat tragedy could have been averted. It is clear there was some conspiracy behind this incident. It is also a matter of concern that there was no prior intelligence available on this conspiracy. Alertness is essential in a democracy. We have been cautious. And if one does not ignore even small incidents like one used to in the past, then one will certainly be successful in fighting terrorism.’

Clearly, Vajpayee was on the defensive, and the Godhra riots deeply worried him. Modi was clearly in his radar.

Clearly, Vajpayee was on the defensive, and the Godhra riots deeply worried him. Modi was clearly in his radar.

But as soon as the national executive committee meet began, Modi surprisingly pre-empted everyone by taking to the dais uninvited and said he would like to step down as chief minister of Gujarat over the riots. Immediately, people from several sides got up and started shouting that there was no need to do so. Whether it was orchestrated or not, nobody was sure, but Vajpayee felt extremely uncomfortable and sensed a coup in the making , according to observers who wrote about this in various books.

Even as the shouting was becoming a chorus an ominous, senior journalist Arun Shourie, who was close to Vajpayee and Advani, described what had gone on between Advani and Vajpayee on the plane on way to Goa and the agreement between the two leaders was that Modi had to resign in the interest of the party.

This created an uproar among the delegates. ‘It cannot be done! Modi cannot be allowed to go!’ Vajpayee immediately understood the situation, and said, ‘Let’s decide on it later.’ ‘It can’t be decided later, it has to be decided now,’ somebody shouted. And as if on cue, it became a slogan.

Throughout the high voltage drama where Vajpayee’s authority was questioned, Advani did not say a word though he knew very well that Vajpayee wanted Modi out. Seeing things take a different turn, Vajpayee kept mum, opting against a confrontational stance. He was clearly worried about younger leaders like Modi publicly questioning his authority.

Throughout the high voltage drama where Vajpayee’s authority was questioned, Advani did not say a word though he knew very well that Vajpayee wanted Modi out. Seeing things take a different turn, Vajpayee kept mum, opting against a confrontational stance. He was clearly worried about younger leaders like Modi publicly questioning his authority.

Analysts say Vajpayee was a crestfallen man and never forgot the humiliation

Also in play was the caste factor. Vajpayee was a Brahmin from Uttar Pradesh and Modi an OBC from Gujarat.

The decision to send Modi out was taken during the flight from Delhi to Goa for the executive committee meeting. In a flight, a very reluctant Vajpayee reportedly briefed his deputy L K Advani. The plan was first, Venkaiah Naidu would replace Jana Krishnamurthi as BJP president. Then he said, ‘Modi has to go.’ By the time they landed in Goa, the decision was taken: Modi would go.

Ironically, it was Vajpayee who made Modi the Chief Minister of Gujarat. In late September 2001, amid massive political infighting, it was decided that Modi would replace Keshubhai Patel as chief minister of Gujarat.

On October 1, 2001, Vajpayee asked Modi to meet him in Delhi. At that time, Modi had lived in Delhi for the previous three years. Unlike Modi, Vajpayee had the habit of putting people at ease before conveying a decision; Modi is blunt and direct.

At the October 1 meeting, Vajpayee joked about how Modi had put on too much weight due to the ‘Punjabi food’ he was having. Even as the two were having a hearty laugh, Vajpayee got to business and asked Modi to go to Gujarat as CM to prepare the state for the next elections due in 2002. Modi did not think twice. He bluntly said no.

Vajpayee insisted and reasoned out the Keshubhai Patel administration had incurred public wrath over not doing enough for the people of the state after the 2001 earthquake. But Modi stood his ground. He told Vajpayee that since he had been away in Delhi as the general secretary in charge of several states, he had been out of touch with local politics. But he agreed to spend ten days a month in the state.

Vajpayee insisted and reasoned out the Keshubhai Patel administration had incurred public wrath over not doing enough for the people of the state after the 2001 earthquake. But Modi stood his ground. He told Vajpayee that since he had been away in Delhi as the general secretary in charge of several states, he had been out of touch with local politics. But he agreed to spend ten days a month in the state.

However, to Vajpayee’s surprise, he called up later and accepted to go to Gujarat as CM. From PM’s residence, Modi had directly gone to meet his mentor Advani. Though Advani knew about Modi’s lack of administrative experience, he was fond of him. He told Modi to take over as the CM. Finally, Modi was sworn in as chief minister of Gujarati on October 7, 2001.

This brings out another difference between Vajpayee and Modi. While Vajpayee was indebted to friends, Modi dumped both Vajpayee and his mentor Advani later.

This also brings out a big and crucial difference — Vajpayee functioned through the BJP and the organisation, while Modi functions outside the BJP creating his own parallel structure of individuals drawn from the RSS, its radical affiliates, and ‘loyalists.’ This group of people swear allegiance to him personally. The loyalist factor can work in small states like Gujarat, but it cannot be extended to cover all of India without serious repercussions on the party and its future.

With loyalists and cheerleaders always around him, Modi is blunt and occasionally uncivil. Vajpayee would never have publicly accused a former prime minister for holding a meeting on Pakistan in Manishankar Aiyar’s house. Similarly, assuming that if loudmouth Aiyar had called Vajpayee neech (which in any case he would never have), Vajpayee would have laughed it off rather than making it a poll issue.

With loyalists and cheerleaders always around him, Modi is blunt and occasionally uncivil. Vajpayee would never have publicly accused a former prime minister for holding a meeting on Pakistan in Manishankar Aiyar’s house. Similarly, assuming that if loudmouth Aiyar had called Vajpayee neech (which in any case he would never have), Vajpayee would have laughed it off rather than making it a poll issue.

Vajpayee was more accommodative and large-hearted. At one of the cabinet meetings, the then Railway Minister Mamata Banerjee walked out in a huff following an altercation with the PM. Vajpayee was very upset. The next day, he was to go on a foreign trip and as per protocol, Mamata was at the tarmac to see Vajpayee off. When Vajpayee approached her, Mamata bent down as usual to touch his feet. But Vajpayee stopped her midway and gave her a long hug. Everything was immediately forgotten.

Modi will never do that. Once an enemy, always an enemy is his belief, right or wrong. Of course, it is another matter that no cabinet minister will dare walk out like Mamata. If he or she does, it would be a permanent walkout.

In fact, Vajpayee had differences with many of the senior leaders in the party, particularly when he became Prime Minister. But he managed these very diplomatically and showed high levels of civility and consultation. He always worked only through the state units of the BJP. But Modi does not believe in this type of consultation. What Amit Shah decides is final. BJP chiefs of State units have very little say.

In fact, Vajpayee had differences with many of the senior leaders in the party, particularly when he became Prime Minister. But he managed these very diplomatically and showed high levels of civility and consultation. He always worked only through the state units of the BJP. But Modi does not believe in this type of consultation. What Amit Shah decides is final. BJP chiefs of State units have very little say.

During Vajpayee’s time, the RSS had a consultative position, but given Vajpayee’s aversion to personalised attacks and threatening postures, it had to function inside some controlled parameters. For instance, the RSS chief at that time could not declare his commitment to a Hindu Rashtra as it is happening now. Modi stresses on Hindu Rashtra and Ram temple wherever possible.

In relying on the BJP and senior party leaders, Vajpayee’s style of functioning was democratic. Modi is more autocratic and dictatorial.

The BJP flourished under Vajpayee. In Modi era, that party has to always nod, not differ. Vajpayee ensured that affiliates like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad and the Bajrang Dal never spewed venom.

Modi is totally the opposite. He works outside the BJP and has his own fleet of loyalists drawn from the RSS, BJP. VHP and others are now part of a parallel structure, now being run by Amit Shah. Modi works closely with the RSS and the affiliate organisations with his victory in the Lok Sabha polls unleashing forces that are carrying out a virulent drive that is affecting the fabric of communal harmony. This is why Modi has maintained a stoic silence when his ranks are accused of religious intolerance.

Modi is totally the opposite. He works outside the BJP and has his own fleet of loyalists drawn from the RSS, BJP. VHP and others are now part of a parallel structure, now being run by Amit Shah. Modi works closely with the RSS and the affiliate organisations with his victory in the Lok Sabha polls unleashing forces that are carrying out a virulent drive that is affecting the fabric of communal harmony. This is why Modi has maintained a stoic silence when his ranks are accused of religious intolerance.

But Vajpayee had a strained relationship with the RSS towards the end of his career as PM. Three months after the Goa meeting in 2002, Advani was elevated as deputy prime minister. Though Advani’s well-wishers had been lobbying in party circles, from the very beginning in 1999, for him to become deputy prime minister, Vajpayee had resisted it. By then, he had assiduously built a wall of moderate leaders around him. These included Jaswant Singh and Brajesh Mishra who rose to become the National Security Advisor.

George Fernandes, a minister but not from the BJP, had been given an important position and Vajpayee also took the support of Nitish Kumar and Andhra Pradesh chief minister Chandrababu Naidu. He did this to primarily keep the RSS lobby at bay. He had also ensured low-key presidents for the BJP like Bangaru Laxman Jana Krishnamurthi and Venkaiah Naidu. These were leaders of state units where the BJP had little support among the electorate. The tactic was to place weak leaderswho could not even get elected from their own states much less challenge Vajpayee at the top.

George Fernandes, a minister but not from the BJP, had been given an important position and Vajpayee also took the support of Nitish Kumar and Andhra Pradesh chief minister Chandrababu Naidu. He did this to primarily keep the RSS lobby at bay. He had also ensured low-key presidents for the BJP like Bangaru Laxman Jana Krishnamurthi and Venkaiah Naidu. These were leaders of state units where the BJP had little support among the electorate. The tactic was to place weak leaderswho could not even get elected from their own states much less challenge Vajpayee at the top.

But in October 2002, a few months after Vajpayee failed to make Modi resign, the RSS demanded a high-level meeting with government representatives and the BJP. Vajpayee was shocked. The meeting was called to review the working of the government and decide on a mid-term course correction. It was a clear message to Vajpayee that he is not the boss and needs to correct himself.

As per newspaper reports of that time, the three major areas where correction was sought were economic policies, which the RSS considered too liberal and anti-Swadeshi; Pakistan, where it said that the government had not been able to counter the moves of that country; and the Ram temple issue. Vajpayee, Advani and Venkaiah Naidu, the BJP president, met a team consisting of the RSS boss KS Sudarshan, joint general secretary HV Seshadri and Madan Das Devi. Although the talks were inconclusive, more importantly, the RSS had got Vajpayee to the discussion table officially which he had been firmly resisting.

Soon after the meeting, the RSS launched a blunt and direct offensive for building the Ram temple. RSS affiliates to joined the chorus. VHP general secretary Giriraj Kishore shocked everyone by openly calling Vajpayee a “pseudo Hindu” who was not assisting in the Ram temple issue. VHP supremo Ashok Singhal declared that Vajpayee was inebriated with power and that he should resign if he could not bring in legislation for the construction of the Ram temple.

Vajpayee brushed all this aside and continued till the end of his term. Analysts say that he believed that on the basis of his stellar economic performance that had led to “India Shining”, he would have won. He was wrong. The Gujarat riots and his failure to rein in Modi led to the BJP losing the 2004 elections.

While Vajpayee believed in consultation, Modi ran Gujarat as an authoritarian leader. The same tendency is on display now in Delhi too. The all-powerful Prime Minister’s Office calls the shots. There are rumours that even the budget is being prepared there and not in the Finance Ministry. Arun Jaitley has to just put his signatures and read it out. True or false, there is a strong perception that Modi’s is the last word on every issue, and he does not like to be tampered with. That was not the case with Vajpayee. Under him, the PMO was a guiding force, not an ordering force or a tough headmaster.

Vajpayee gave a free hand to his ministers. In fact he did not interfere in the functioning of Ministries either, except in his role of a guide and mentor and the first amongst equals in the Cabinet as per the Indian Constitution.

Modi, on the other hand, does not trust anyone, and probably, including his own shadow.

Of course, the ministers consulted Vajpayee more as a friend and father figure. His external affairs minister and finance minister Jaswanth Singh and Yashwant Sinha had freedom to take decisions. But in Modi’s dispensation, there is a namesake External Affairs Minister in Sushma Swaraj whose only job is to tweet and rescue stranded Indians. No policy decisions are left to her. Modi is for all purposes the External Affairs Minister and Finance Minister. He is not comfortable handling Defence and so he has let that portfolio go to Nirmala Sitaraman, who again, does not take any decisions without a nod from the all-powerful PMO.

It is said that Modi heads a Government where Rank 1 to 10 in his Cabinet are all occupied by him. He holds absolute authority over his cabinet and his stamp on his Government is final. He runs a much younger Government and his authority is unchallenged. His colleagues fear him.

It is said that Modi heads a Government where Rank 1 to 10 in his Cabinet are all occupied by him. He holds absolute authority over his cabinet and his stamp on his Government is final. He runs a much younger Government and his authority is unchallenged. His colleagues fear him.

Vajpayee’s PMO was like a happy family where people worked together in complete trust of the Prime Minister. Modi’s PMO is like Corporate Headquarters where the emphasis is on long-term planning, delivery, performance and deadlines. Modi’s bureaucrats know who the boss is, whom they are accountable to. The chances of fumbles are minimal. Nothing goes unnoticed from the PMO’s hawk eyes. Vajpayee was magnanimous in his dealings. He could be forgiving, benevolent and accommodative. Not Modi. He is a hard task master who knows how to make use of the system and use it to his advantage. He may trust someone one day and throw him out the next day if he or she under performs. Little wonder that there was not a murmur when sacked under performers during a cabinet reshuffle.

Being in complete control, many wonder if Modi would have taken a different decision in the 1999 Kandahar hijack crisis of an Indian Airlines flight had he been the PM. Some say Vajpayee succumbed to pressure too fast and too soon allowing a major terrorist to be freed.

Militants of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, a Pakistan-based extremist group, brought India on its knees hijacking Flight IC 814 in Indian airspace to Kandahar. To end the hostage crisis, the government led by Vajpayee surrendered before terrorists and agreed to release three militants, who later planned and executed 9/11 attacks, the kidnap and murder of Daniel Pearl and 2006 Mumbai terror attacks.

The failure of the Vajpayee government during the Kandahar hostage crisis will always remain a blot on Indian history. Modi may have dealt with the crisis in a different manner, many say more in hindsight.

Some say that Modi, unlike Vajpayee, is lucky running a majority Government. But such critics obviously have forgotten the most punishing and disciplined campaign Modi ran for his election. He addressed 437 rallies, travelled more than 3 lakh km in a period of 8 months for getting that number. Forget the many Chai pe Charchas, 3D rallies and the interviews he gave. So, he is not lucky. He worked for that number and he got that number.

Modi has a tight control over the government. He does not consult, he orders. He does not like people to approach him, he approaches who he needs to speak with. There is an interesting story here which points to this authoritarian side.

The story that did the rounds some time ago suggested a fall from grace of industrialist Mukesh Ambani. When he was introducing his wife to the Prime Minister, he made the mistake of placing his hand on Modi’s back. In fact a photograph of Modi with the couple captures this. Bureaucratic grapevine says this angered the Prime Minister who immediately distanced himself from Ambani.

Modi also has zero tolerance for criticism, controlling the BJP with an iron fist through his Man Friday and party president Amit Shah. Vajpayee was open to criticism and dismissed most of them with a shayar or humour.

But there is a difference. Vajpayee headed a coalition and he was probably forced to be accommodative. It is debatable that assuming Vajpayee had the same majority as Modi has today, would he have steamrolled demonetisation and the GST? But would Modi change and be forced to be accommodative if he is forced to head a coalition in the next election is debatable.

Vajpayee had close friends who were not with the RSS. Modi has none, except Amit Shah. Vajpayee’s friends spent evenings with him with some candid talk which the PM listened to carefully. One of them was Brajesh Mishra. He enjoyed freedom as well as clout from his proximity to the then Prime Minister.

Vajpayee had close friends who were not with the RSS. Modi has none, except Amit Shah. Vajpayee’s friends spent evenings with him with some candid talk which the PM listened to carefully. One of them was Brajesh Mishra. He enjoyed freedom as well as clout from his proximity to the then Prime Minister.

Vajpayee also liked to take the advice of several ‘intellectuals’ with a wide variety of retired bureaucrats, editors, columnists, academics who used to frequent the PMO during his days. This was quite unlike Modi who dislikes meeting people with other points of view. His interactions amongst the BJP leaders itself are minimalist from all records.

Modi likes media coverage and spends a great deal in giving advertisements to the print media and television news channels. But he loathes meeting the media and treats journalists with disdain. As BJP general secretary, Modi had many friends in the media. But when he assumed power, he at best lets out a stern smile; no interaction.

Vajpayee had an active media advisor in Ashok Tandon who was accessible to all, including BJP critics in the media. There were several interactions with Vajpayee at the time. After coming to power, Vajpayee hosted a luncheon for senior journalists at the official residence; critics were specially invited. After the lunch, he sat back and took a volley of questions on all possible issues from the scribes.

Modi, on the other hand, had his first interaction with journalists at the BJP headquarters where all posed for a selfie, and no awkward questions were asked. As one journalist who attended the meeting said later, “no one dared as he has such a foreboding presence.”

But to the credit of Modi, it should be said that elections are won across states because of him alone. Vajpayee, on the other hand, was always one of the campaigners sharing his dais with other BJP seniors, even with adversaries like Advani. The difference: During Vajpayee’s regime, the BJP campaigned in elections, now it is just Modi, not the BJP.

The difference between the two BJP Prime Ministers is not about ideology. They both believe in the same ideology propounded by the RSS, in the same forefathers, the same mission, and the same goal. Both were and are RSS pracharaks. The difference is in style and approach. Vajpayee was astute enough to wear the ‘mask’ of democracy without ever letting it slip. In Modi’s case it slips all too often showing shades of authoritarian streak.

This is dangerous for democracy in the long run. As it said, power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

But credit should also be given to Modi that the BJP as a party has grown at a much faster pace under his leadership compared to Vajpayee. Modi has nearly vanquished and threatened the very existence of his opponents as well as his allies. That is one of the main reasons why the opposition parties are grouping together in the form of mahagatbandhans or of caste and communal groupings.

Unlike Vajpayee, many people across India are praying for Modi – either for his failure or his success.

But in the end, how will history judge the two leaders? Undoubtedly, Vajpayee will be seen as a statesman with a large heart. But Modi is not chasing that legacy. He is least bothered about that legacy. He wants to leave behind his own legacy where he himself is his competition. He wants to be a modern Sardar Patel – strong, strict and wants an India that is strong and a superpower.

Vajpayee was rooted in the present; Modi is anchored in future. But to be fair, it is too early to make a complete assessment on Modi. That would probably be possible a decade after the 2019 general elections. But surely, he is keen to build a superstructure over the legacy left behind by Vajpayee.

Read More News;

- Donald Trump Reignites Jerusalem Powder Keg, Sparks Turmoil in Middle East

- Tipu Sultan `Storms’ Into Political Fray in Karnataka

- Privacy Will Not Stand `Naked’ if Mobile Numbers Are Linked to Aadhar

- When You’re Tired, Your Brain Cells Actually Slow Down

- Finders Keepers To Hit Screens on November 24

- With a Boring Speech, Xi Jinping Wants to Make China Big Brother-II

- Life, Death and Sex

- Is Finance Minister Arun Jaitley Being Sidelined?

- Unsung Martyrs of Freedom Struggle To Get a `Voice’

- Tesla Fires Hundreds in One Go Over Poor Performance